Fall Turfgrass Disease Prevention and Control

by Alfredo Martinez

Large Patch

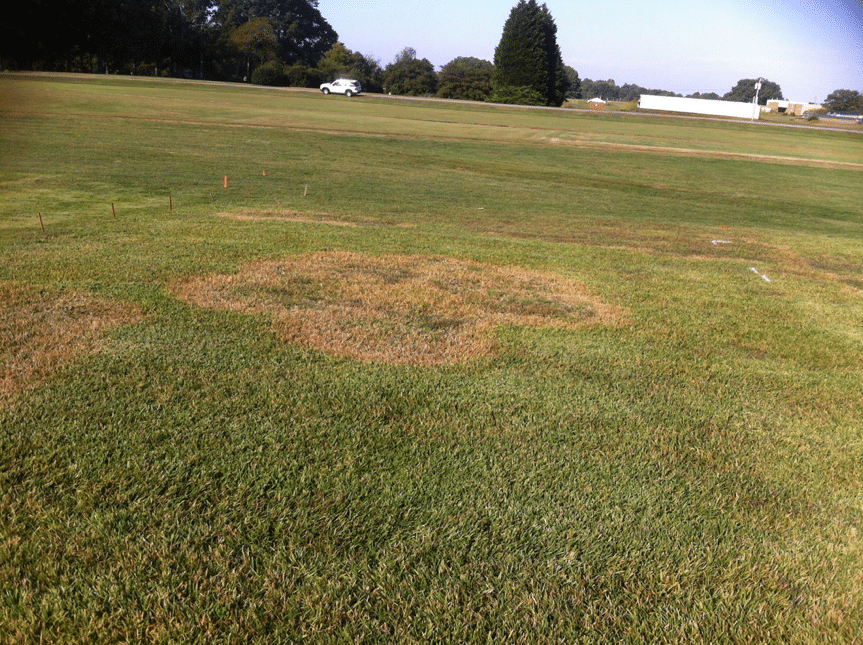

Rhizoctonia large patch is the most common and severe disease of warm season grasses (bermudagrass, centipedegrass, seashore paspalum, St. Augustinegrass, and zoysiagrass) across the state of Georgia. Due to spring and fall disease-promoting environmental conditions across Georgia coinciding with grasses leaving and/or entering dormancy, large patch can appear in warm season grasses in various grass-growing settings, including home lawns, landscapes, sports fields, golf courses, and sod farms. Symptoms of this lawn disease include irregularly-shaped weak or dead patches that are from 2 feet to up to 10 feet in diameter. Inside the patch, you can easily see brown sunken areas. On the edge of the patch, a bright yellow to orange halo is frequently associated with recently affected leaves and crowns. The fungus attacks the leaf sheaths near the thatch layer of the turfgrass.

Large patch disease is favored by:

- Thick thatch.

- Excess soil moisture and poor drainage.

- Too much shade, which stresses turfgrass and increases moisture on turfgrass leaves and soil.

- Early spring and late fall Nitrogen fertilization.

If large patch was diagnosed earlier, fall is the time to control it. There is a myriad of fungicides that can help to control the disease. Fungicides in the following classes are labeled for large patch control: carboxamides, benzimidazoles, carbamates, dicarboximides, DMI fungicides, di-nitro anilines, control. For a complete and updated list of fungicides available for commercial control of large patch, visit http://extension.uga.edu/publications/detail.cfm?number=SB28 or http://www.commodities.caes.uga.edu/turfgrass/georgiaturf/Publicat/1640_ Recommendations.html. Preventative or curatives (depending on the particular situation) rates of fungicides in late September or early October and repeating the application 28 days later are effective for control of large patch during fall. Fall applications may make treating in the spring unnecessary. Always follow label instructions, recommendations, restrictions and proper handling.

Cultural practices are very important in control. Without improving cultural practices, you may not achieve long term control.

- Use low to moderate amounts of nitrogen, moderate amounts of phosphorous and moderate to high amounts of potash. Avoid applying nitrogen when the disease is active.

- Avoid applying N fertilizer before May in Georgia. Early nitrogen applications (March-April) can encourage large patch.

- Water timely and deeply (after midnight and before 10 AM). Avoid frequent light irrigation. Allow time during the day for the turf to dry before watering again.

- Prune, thin or remove shrub and tree barriers that contribute to shade and poor air circulation. These can contribute to disease.

- Reduce thatch if it is more than 1 inch thick.

- Increase the height of cut. Reduced mowing heights result in a more dense turf stand, which may create a more favorable environment for large patch development

- Improve the soil drainage of the turf.

- Control traffic patterns to prevent severe compaction, and core aerate to improve soil drainage and increase air circulation around the shoots and root

For more information on large patch visit https://secure.caes.uga.edu/extension/publications/files/pdf/C%201088_2.PDF

Spring Dead Spot of Bermudagrass

Fall cultural practices and fungicide applications are key for Spring Dead Spot management. The disease is caused by fungi in the genus Ophiosphaerella (O. korrae, O. herpotricha and O. narmari). These fungi infect roots in the fall predisposing the turf to winter kill. As indicated by its name, initial symptoms of spring dead spot are noticeable in the spring, when turf resumes growth from its normal winter dormancy. As the turf ‘greens-up,’ circular patches of turf appear to remain dormant, roots, rhizomes and stolons are sparse and dark-colored (necrotic). No growth is observed within the patches. Recovery from the disease is very slow. The turf in affected patches is often dead; therefore, recovery occurs by spread of stolons inward into the patch. The causal agents of SDS are most active during cool and moist conditions in autumn and spring. Appearance of symptoms is correlated to freezing temperatures and periods of pathogen activity. Additionally, grass mortality can occur quickly after entering dormancy or may increase gradually during the course of the winter. Spring dead spot is typically more damaging on intensively managed turfgrass swards (such as bermudagrass greens) compared to low maintenance areas.

- Practices that increase the cold hardiness of bermudagrass generally reduce the incidence of spring dead spot. Severity of the disease is increased by late-season applications of nitrogen during the previous fall.

- Management strategies that increase bermudagrass cold tolerance such as applications of potassium in the fall prior to dormancy are thought to aid in the management of the disease. However, researchers have found that fall applications of potassium at high rates actually increased spring dead spot incidence. Therefore, application of excessive amounts of potassium or other nutrients, beyond what is required for optimal bermudagrass growth, is not recommended.

- Excessive thatch favors the development of the disease. Therefore, thatch management is important for disease control,

- Implement regular dethatching and aerification activities.

- There are several fungicide labeled for spring dead spot control.

- Timing, selection and application of fungicides are important for preventative management of SDS. Fungicide application in the fall when soil temperatures are between 60° and 80° F provides the best control of SDS

- A complete list of fungicides, formulations and product updates for SDS can be found in the annual Georgia Pest Management Handbook and the Turfgrass Pest Control Recommendations for Professionals (http://www.georgiaturf.com). Some fungicide options are exclusively for golf course settings. Always check fungicide labels for specific instructions, restrictions, special rates, recommendations, follow-up applications and proper handling.

For more information on SDS visit https://secure.caes.uga.edu/extension/publications/files/pdf/C%201012_3.PDF

Early detection of bermudagrass leaf spot

Severe leaf and crown rot, caused by Bipolaris ssp. can occur in bermudagrass lawns, sport fields, or golf fairways. Initial symptoms of this disease include brown to tan lesions on leaves. The lesions usually develop in late September or early October. Older leaves are most seriously affected. Under wet, overcast conditions, the fungus will begin to attack leaf sheaths, stolons and roots resulting in a dramatic loss of turf. Shade, poor drainage, reduced air circulation; high nitrogen fertility and low potassium levels favor the disease. To achieve acceptable control of leaf and crown rot, early detection (during the leaf spot stage) is a crucial.

Dollar spot is still active in the fall/early winter

Dollar spot is most prevalent during spring and fall with infections developing rapidly at temperatures between 60 and 75 degrees Fahrenheit combined with long periods of leaf wetness from dew, rain, or irrigation.

- Excessive moisture on turfgrass foliage will promote dollar spot epidemics. Irrigating in the late afternoon or evening should be avoided, as this prolongs periods of leaf wetness.

- If feasible, prune or remove trees and shrubs to promote air movement and accelerate drying of the turfgrass canopy

- A variety of fungicides are available to professional turfgrass managers for dollar spot control including fungicides containing benzimidazoles, demethylation inhibitors

(DMI), carboximides, dicarboximides, dithiocarbamates, nitriles and dinitro-aniline. Several biological fungicides are now labeled for dollar spot control.

- For a complete and updated list of fungicides available for dollar spot, visit http://extension.uga.edu/publications/detail.cfm?number=SB28 or http://www.commodities.caes.uga.edu/turfgrass/georgiaturf/Publicat/1640_Recommendations.htm.

Additional information on dollar spot visit https://secure.caes.uga.edu/extension/publications/files/pdf/C%201091_2.PDF