Where, oh where, does the virus go (in the winter)?

Dr. Rosmarie Kelly, Public Health Entomologist, Georgia Department of Public Health

It’s that time of year when those in mosquito surveillance and control think fondly of consistently cooler temperatures and eagerly await that first hard frost. Of course, this is already happening in some places up north. We may have to wait a while longer in here in Georgia. But that does bring to mind the question: Where do all the mosquitoes go once the colder weather arrives?

Mosquitoes, like all insects, are cold-blooded creatures. As a result, they are incapable of regulating body heat and their temperature is essentially the same as their surroundings. Mosquitoes function best at 80 F, become lethargic at 60 F, and cannot function below 50 F. In tropical areas, mosquitoes are active year round. In temperate climates, mosquitoes become inactive with the onset of cool weather and enter diapause (hibernation) to live through the winter. Diapause induction also requires a day length shorter than 12 hours light (more than 12 hours dark). All mosquitoes pass through four developmental stages: egg, larva, pupa and adult, and diapause can occur in any of these stages depending on the species.

- The Aedes and Ochlerotatus species, and some Culiseta species, lay eggs in dry or damp, low-lying areas or containers that are subject to flooding from accumulations of precipitation. Winter is passed in the egg stage, with hatching dependent on the presence of water, water temperature, and amounts of dissolved oxygen.

- Coquillettidia and Mansonia species, and some Culiseta species, have larval stages that overwinter, apparently without total loss of activity, restricting development to very permanent water bodies. These species renew development towards the adult stage once water temperatures begin to rise.

- Overwintering in Anopheles, Culex and some Culiseta species takes place in the adult stage by fertilized, non-blood-fed females. In general, these mosquitoes hide in cool, dark places waiting for temperatures to rise and days to lengthen before they seek out a blood meal and resume their lives.

What, if anything, does this mean for West Nile virus (WNV)? If the mosquitoes are infected with WNV when they enter diapause, it should overwinter with them to be transmitted to birds when the mosquitoes emerge the following spring. Temperature is the crucial factor in the amplification of the virus. Studies in various states have shown that WNV does indeed overwinter in mosquitoes. The virus does not replicate within the mosquito at lower temperatures, but is available to begin replication when temperatures increase. This corresponds with the beginning of the nesting period of birds and the presence of young birds. Circulation of virus in the bird populations allows the virus to amplify until sufficient virus is present in the mosquito populations (and vector mosquito populations are high enough) that horse and human infections begin to be detected.

In the Northeastern U.S., Culex pipiens, the northern house mosquito, is the most important vector species. This species overwinters as an adult, and has been found harboring WNV during the winter months. This mosquito goes into physiological diapauses (akin to hibernation) during the winter months, and while it may be active when temperatures get above 50°, it will not take a blood meal.

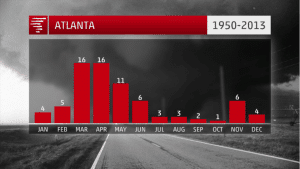

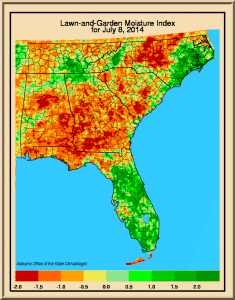

Culex quinquefasciatus, the southern house mosquito and the major vector for WNV in Georgia, also overwinters as an adult, and also goes into diapause when winter comes, and it is likely that this mosquito also harbors WNV throughout the winter months. However, the southern house mosquitoes go into more of a behavioral diapause when temperatures are below 50°, and are quite capable of taking a blood meal (and maybe transmitting WNV) when things warm up during the winter, which is not an unlikely occurrence here in Georgia especially as one goes further south. So, although the risk for WNV transmission in the south in the winter months is very low, it is certainly possible.