Are you especially concerned about mosquitoes this summer as you work in your garden? Do you wonder how to care for your bird baths so that your birds are happy but you are not creating a breeding pond for mosquitoes? We had the opportunity to talk with University of Georgia’s mosquito specialist, Elmer Gray, and asked him for some research-based mosquito information.

Asian Tiger mosquito

Tiger, tiger…Aedes albopictus

Taken from the April 10 issue of Dideebycha, newsletter of the Georgia Mosquito Control Association

Aedes albopictus was introduced into the Port of Houston in 1985 in shipments of used tires from northern Asia. Movement of tire casings has spread the species to more than 20 states since 1985.

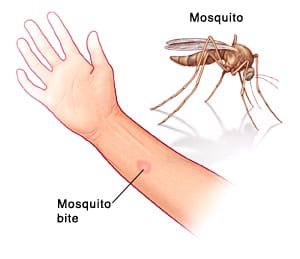

The Asian tiger mosquito is a small black and white mosquito. The name “tiger mosquito” comes from its white and black color pattern. It has a white stripe running down the center of its head and back with white bands on the legs. These mosquitoes lay their eggs in water-filled natural and artificial containers like cavities in trees and old tires; they do not lay their eggs in ditches or marshes. The Asian tiger mosquito usually does not fly more than about ½ mile from its breeding site and generally flies a considerably shorter distance.

Aedes albopictus associates closely with people and is an aggressive, daytime biting mosquito. It is native to the tropical and subtropical areas of Southeast Asia, and is now found in 1/3 of the Unites States. New Jersey, southern New York, and Pennsylvania are currently the northernmost boundary of established Ae albopictus populations in the eastern United States.

The tiger mosquito is an important disease carrier in Asia. In North America, Ae albopictus is among the most efficient bridge vectors of WNV. In addition to vectoring exotic arboviruses, this species can also transmit the endemic eastern equine encephalitis and La Crosse viruses in the laboratory and in the field. It is a competent vector of both Dengue and Chikungunya virus. In fact, Ae albopictus is a competent vector for at least 22 arboviruses.

A lot of work has been done recently on control of Ae albopictus. Since it is a daytime biting species and an asynchronous emerger, conventional truck-based ULV spraying doesn’t always work well. According to one study, an integrated pest management approach can affect abundances, but labor-intensive, costly source reduction is not enough usually to maintain Ae albopictus counts below a nuisance threshold.

References

Fonseca, et al, Area-wide management of Aedes albopictus. Part 2: Gauging the efficacy of traditional integrated pest control measures against urban container mosquitoes. 2013. Pest Management Science, 69 (12): 1351–1361.

Insects and Cold Weather

Elmer Gray, University of Georgia, Entomology Department

With this winter’s unusually cold temperatures, the question of how these conditions affect insects is sure to arise. It is of little surprise that our native insects can usually withstand significant cold spells, particularly those insects that occur in the heart of winter. Insect fossils indicate that some forms of insects have been in existence for over 300 million years. As a result of their long history and widespread occurrence, insects are highly adaptable and routinely exist and thrive, despite extreme weather conditions. Vast regions of the northern-most latitudes are well known for their extraordinary mosquito and black fly populations despite having extremely cold winter conditions.

The question then arises, how do insects survive such conditions? In short, insects survive in cold temperatures by adapting. Some insects, such as the Monarch Butterfly migrate to warmer areas. However, most insects use other techniques to survive the cold.

In temperate regions like Georgia, the shortening day length during the fall stimulates insects to prepare for the inevitable winter that follows. As a result, many insects overwinter in a particular life stage, such as eggs or larvae. Many mosquitoes overwinter in the egg stage, such as our common urban pest the Asian Tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus), waiting for warmer temperatures and sufficient water levels to hatch in the spring. Another technique is to take advantage of protected areas, as do adult Culex mosquitoes overwintering in the underground storm drain systems. Other insects overwinter as larvae or pupae in the soil, protected from the most extreme temperatures. However, this still doesn’t answer how insects survive freezing temperatures, only to become active as warmer temperatures return.

All insects have a preferred range of temperatures at which they thrive. As the temperature drops below this range the insects become less active until they eventually cannot move. A gradual decline in temperatures, coupled with a shortening day length, serves to prepare an insect to tolerate freezing temperatures. Several factors are important to this tolerance.

The primary thing that an insect has to avoid is the formation ice crystals within their body. Ice crystals commonly form around some type of nucleus. As a result, overwintering insects commonly stop feeding so as to not have food material in their gut where ice crystals can form. This reduction in feeding will also result in a reduction in water intake.

A degree of desiccation increases the concentration of electrolytes in the insect hemolymph (blood) and tissues. In addition, insects that can tolerate the coldest of temperatures often convert glycogen to glycerol. These electrolytes and glycerol create a type of insect antifreeze. This will lower the freezing point of the insect to well below freezing, a condition described as supercooling. When this occurs, the insect can withstand extremely cold temperatures for extended periods.

However, at some point insects will suffer increased mortality, possibly due to desiccation, toxicity or starvation. Nevertheless, insects are well adapted to survive freezing temperatures, especially after a few 100 million years to perfect their systems. It is generally assumed that introduced pest insects from sub- and tropical areas would be more susceptible to extended cold spells, but depending on their ability to find local refuges and their numbers and adaptability, they likely will remain viable and persist as pests as well.

In summary, entomologists don’t expect the cold winter to have a significant impact on insect populations this spring. Local conditions related to moisture and overall seasonal temperatures (early spring/late spring) will play a much more important role in insect numbers as we move from winter to summer and prepare for the insects that will be sure to follow.