Source(s): Gil Landry, PhD., Coordinator- The Center for Urban Agriculture, The University of Georgia.

Georgia’s landfills are filling up and closing at an alarming rate, and citizens everywhere are recycling to help them last longer. Grasscycling, the natural recycling of grass clippings by leaving them on the lawn when mowing instead of bagging them, is proving to be a simple and effective way to save landfill capacity while saving you time, work and money in the landscape.

Grasscycling Saves Time

A study in Texas found that grasscycling meant an extra mowing per month but required 35 minutes less time per mowing. After six months of grasscycling, homeowners who took part in the study have saved an average of seven hours of yard work.

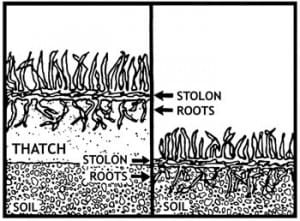

Grasscycling Does Not Cause Thatch

In the early 1960s, it was commonly believed that grass clippings were a major part of thatch and that removing clippings would slow thatch development. However, research later determined that thatch buildup is caused by grass stems, shoots and roots. The clippings are rapidly decomposed and valuable nutrients are released into the soil.

Proper Mowing

Proper mowing is the key to successful grasscycling. This includes cutting the grass at the recommended height, maintaining a sharp mower blade, mowing when the grass i dry, and mowing often enough to remove no more than one-third of the plant height. If tall fescue, for instance, is being kept at two inches, it should be mowed when it reaches three inches. This generally requires mowing every five days instead of every seven days. If the grass becomes too tall between mowings, raise the cutting height for the first mowing and then gradually lower it with later mowings until the proper height is reached. During stress periods, such as summer drought, raise the cutting height but continue mowing often enough to avoid excess leaf removal.

All mowers can grasscycle and no special equipment is needed. However, many lawnmower manufacturers sell mower attachments that chop clippings into smaller pieces and improve a mower’s grasscycling performance.

| Mowing Heights | |

| Centipedegrass | 1 to 1.5 inches |

| Common bermudagrass | 1 to 2 inches |

| Hybrid bermudagrass | 0.5 to 1.5 inches |

| Tall fescue | 2 to 3 inches |

| St. Augustine grass | 2 to 3 inches |

| Zoysiagrass | 0.5 to 1.5 inches |

Proper Fertilization

A fertilization program should be based on turfgrass needs, soil tests, maintenance practices, and desired appearance. An analysis of your soil can be obtained through your local county Extension office. In the absence of a soil analysis, two widely used fertilizers for turf are 16-4-8 and 12-4-8. Six pounds of 16-4-8 per 1,000 square feet of lawn area or eight pounds of 12-4-8 per 1,000 square feet will provide the recommended rate of one pound of nitrogen per application. The table below will provide suggested application frequencies for these fertilizers. A dark green well-fertilized turf is attractive, but it also requires more frequent mowing and irrigation. If turf growth is too fast for your mowing frequency, you may need to reduce the amount of fertilizer applied by one-third to one-half. On well-established and well-maintained lawns, lower rates are often adequate.

Water Management

Established lawns often need irrigation to maintain good color and growth. Turf grasses generally require more water in hot weather, but may also need water in cool periods. Grasses in need of water appear dull bluish green and leaf blades begin to fold or roll. Lawns should not be watered until these moisture stress symptoms are seen. To save water and avoid turf diseases, the best time to water is between sunset and sunrise. Apply enough water to soak the soil to a six to eight inch depth. This is usually equivalent to one inch of rainfall or 600 gallons of water per 1,000 square feet.

Grasscycling is a proven and effective method of lawn management. It also provides an environmentally important opportunity for all Georgia citizens to participate in curbside waste reduction.

Resource(s): Lawns in Georgia

Center Publication Number: 91